Orazio Borgianni (1574–1616) – a melancholic with intellectual ambitions and an explosive character

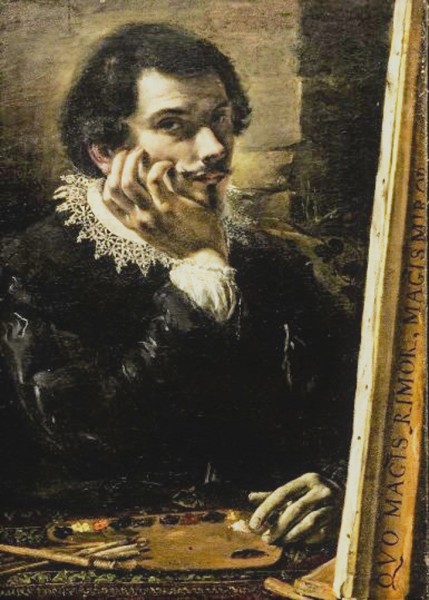

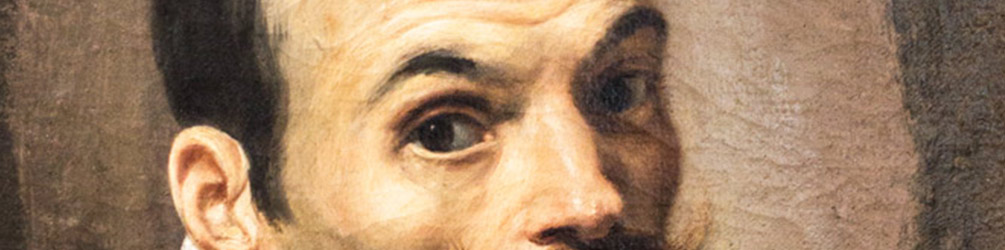

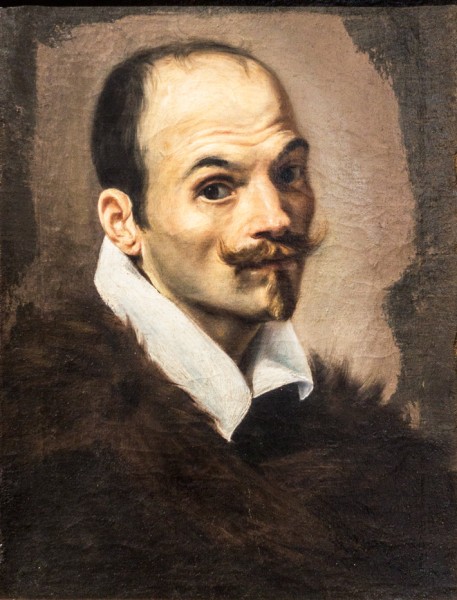

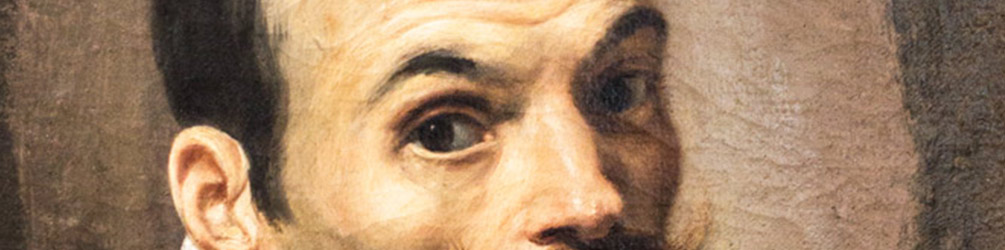

Orazio Borgianni, self-portrait from his youth, private collection

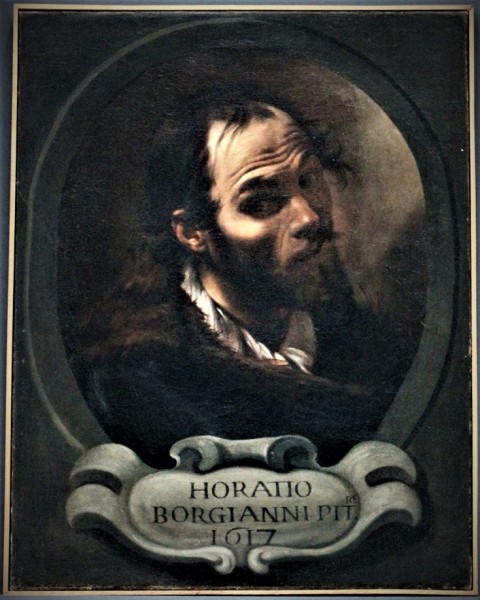

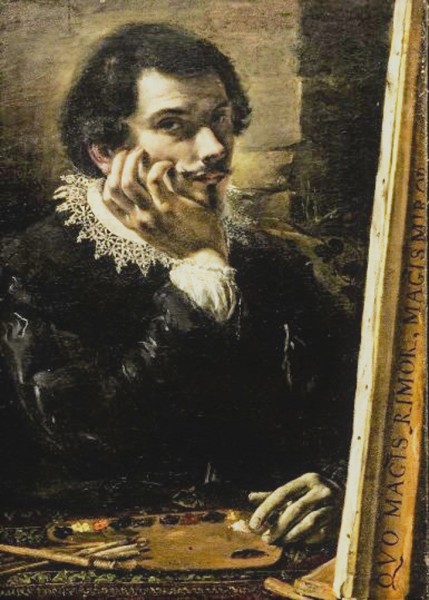

Orazio Borgianni, Self-Portrait, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca

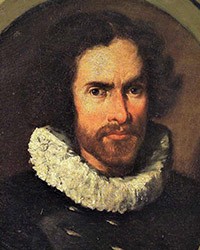

Gallery of great painters, Borgianni's self-portrait - first on the left, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca

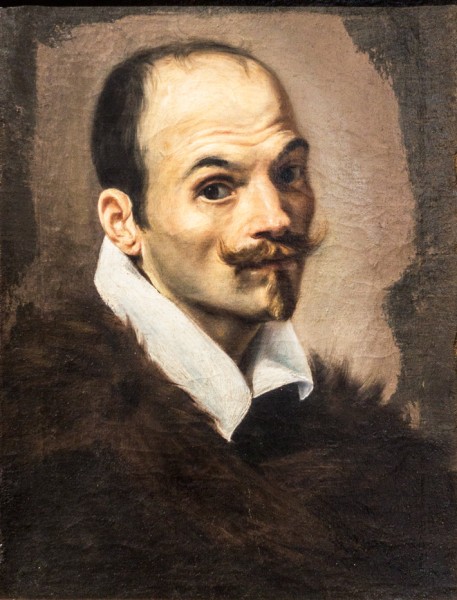

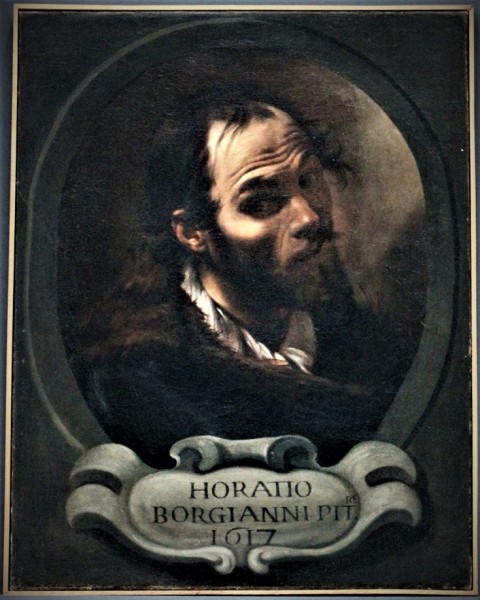

Orazio Borgianni, Self-portrait, Galleria Nazional d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

Orazio Borgianni, Holy Family with St. Elizabeth and St. John the Baptist, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

Orazio Borgianni, Charles Borromeo adoring the Holy Trinity, sacristy of the Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

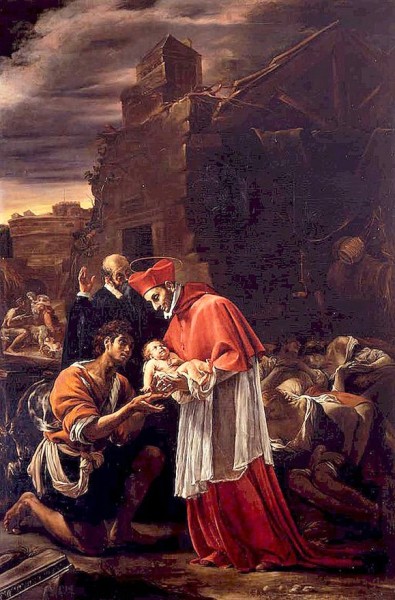

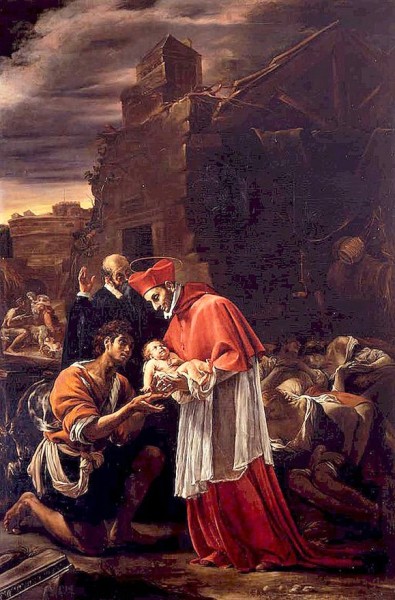

Orazio Borgianni, Charles Borromeo among the plague-ridden, Curia Generalizia dell'Ordine della Mercedario, pic.Wikipedia

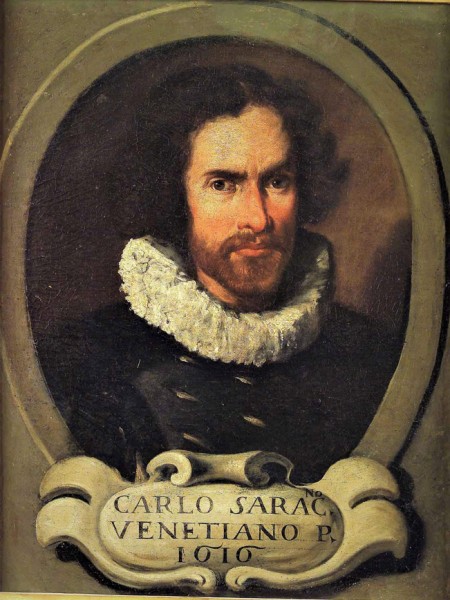

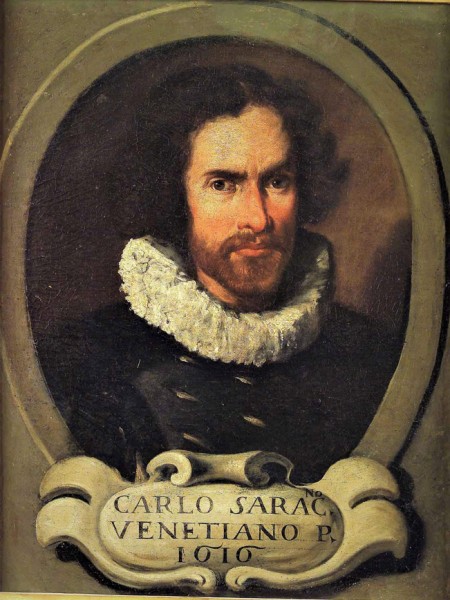

Orazio Borgianni, portrait of Carlo Saraceni, Accademia di San Lucca, pic. Wikipedia

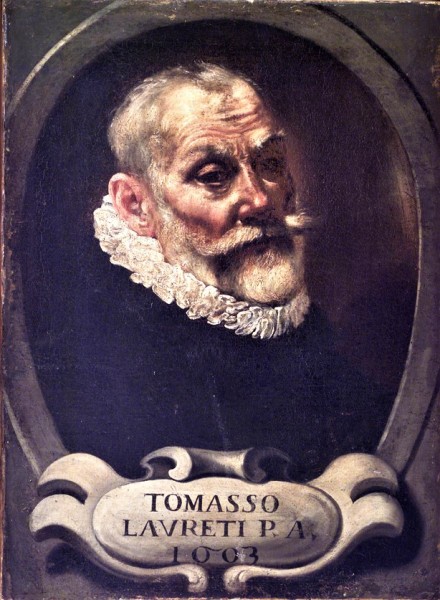

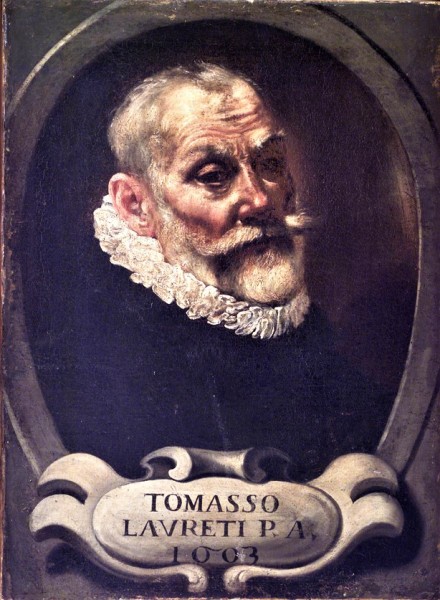

Orazio Borgianni, portrait of Tommaso Laureti, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca

In 2020 a self-portrait of an artist of exceptional beauty appeared on the antique market. A young, handsome man rests his chin on his hand and looks at us with a melancholic gaze, as if he had for a moment halted the work on the canvas in front of him. It seems that he is deep in thought, but what is he pondering? Perhaps the words QUO MAGIS RIMOR, MAGIS MIROR (The more I seek the more I am amazed), which we can notice on the frame of the painting. What could they mean?

In 2020 a self-portrait of an artist of exceptional beauty appeared on the antique market. A young, handsome man rests his chin on his hand and looks at us with a melancholic gaze, as if he had for a moment halted the work on the canvas in front of him. It seems that he is deep in thought, but what is he pondering? Perhaps the words QUO MAGIS RIMOR, MAGIS MIROR (The more I seek the more I am amazed), which we can notice on the frame of the painting. What could they mean?

In order to find the answer to this question, we must delve into Borgianni’s biography. Until recently we did not know too much about him. The monographic exhibition organized in 2020 in the Roman Palazzo Barberini, brought us closer to the works of this artist from his time in the city on the Tiber, at the same time showing the multifaceted spectrum of his painting abilities. Yet it was not Rome where he began his short career, but he did finish it there.

At the time of painting the self-portrait Borgianni was only slightly over thirty years old but he was already an experienced artist. He had lived in Sicily, a time we know very little about, but above all, he had spent nearly ten years in Spain. There he got married and became famous for painting altarpieces in such cities as Pamplona, Saragossa, Toledo, and Madrid. However, from time to time he returned to his birthplace of Rome to finally come back for good at the end of 1605 after the death of his wife. He was still involved with Spanish collectors and art enthusiasts while his principal patron was the Spanish ambassador Francisco Ruiz de Castro, who had resided in Rome. He also became a member of the prestigious Academy of St. Luke, and he was the auditor of this institution in the years 1606-1607 and in 1607 even its first rector. He was also a member of other significant scientific and academic circles in the Eternal City (Accademia degli Umoristi i Accademia dei Virtuosi al Pantheon), where he met with intellectuals, erudites, and writers. Even in Spain, where his status was much lower than in Italy, Borgianni exhibited the ambition to surround himself with educated people and at the same time to create structures with the goal to elevate his social status. He tried to establish something like an academy in Spain, which would bring together artists as was the case in Italy. His contacts with the Italian intellectual elite are a testimony to his sublime interests, ones that greatly exceeded those exhibited by his contemporary painters, that were generally limited to becoming familiar with the secrets of their profession. It was when in contact with those groups of people, that Borgianni was able to acquire knowledge that was not accessible to just anyone, knowledge that left him amazed. The sentence on the frame from the aforementioned self-portrait was most likely a loud exclamation of amazement over the world, which is definitely much more complex than it would appear to the average man, living at the beginning of the XVII century, and that is probably what the painter discovered in his meetings with scholars. Let us recall the several months that Galileo had spent in Rome in 1611 when he was invited by the members of the renowned Accademia di Licei, and the ferment but also amazement with which his theories regarding the planets were listened to. These were the theories that perhaps our protagonist listened to as well.

However, Borgianni was not only a melancholic interested in the world of science. Shortly after coming to the Eternal City, his surname found itself in police reports. Along with his fellow painter, Carlo Saraceni, he was accused of co-participating in an assassination attempt (reportedly planned by Caravaggio) on the life of another fellow painter – Giovanni Baglione. The matter is difficult to explain. Some researchers speculate that the Baglione, who was not liked by Caravaggio’s friends desired to have them removed from the Academy of St. Luke. However, Borgianni was not part of "Caravaggio's fraction", which he himself mentions in describing a situation in which he threw a bottle of varnish at Caravaggio when the painter ridiculed him for some reason. Such an episode was not something unusual in those times. In the Roman artistic community, quarrels out of envy and jealousy were quite common. And it was not only bottles of varnish that were the weapons of choice but epees, and daggers as well. The bond that connected both painters was most likely the sensation of self-worth and a quasi-aristocratic pride, which they defended vehemently. Indeed, Borgianni similarly to Caravaggio had a very explosive, independent, and ill-behaved temperament. As Baglione emphasized in his tome of biographies (La vitae dei pittori…,1642), this was “a free man, (…) courageous, and generous, who did however, have problems with colleagues, authority figures, and nobles”.

Regardless of the personal relationship between Borgianni and Caravaggio, Michelangelo Merisi's painting fascinated everyone, and the renown he gained in Rome was so great that no artist could be oblivious to his paintings. Borgianni also found himself under his influence, although only briefly. He, like others, was also affected by Caravaggio's strong illuminating effects and naturalism, although they never played a dominant role in his elegant paintings, which were in truth marked by the impulses taken from late Tintoretto and El Greco.

When Borgianni came to Rome he was already a painter with a set and well-developed style, manifesting itself in typical for him quivering compositions and slightly elongated proportions of the human figures placed in his paintings His canvases were full of vigor, motion, and expression, while their language was characterized by the use of using distant layouts and a narrative method of presenting the topic with a great number of figures.

In the city on the Tiber, Borgianni left but a few works. They do not reflect his unbelievable talent in full, but they do constitute important stages in his artistic development and are a testimony of the effort of smuggling symbolic ideas hidden behind simple objects or gestures which can be seen for example in the painting Holy Family with St. Elizabeth, the Young St. John the Baptist and an Angel in the Palazzo Barberini (Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Artica).

In history, he will be remembered as the creator of the image of the man who attained sainthood at that time (1610) Cardinal Charles Borromeo. Depicting the saint with his hand placed upon his chest and his eyes directed towards the heavens would from then on be duplicated in a limitless number of paintings, inspired by Borgianni's canvas almost attaining the status of an iconographic type.

Between the years 1614 and 1615, the artist portrayed himself once again – this time among the members of the Academy of St. Luke. In this image, we can see a visage that is tired, sunken, twisted, and with unkempt hair. This is how Borgianni wished to be remembered. For some, it was a demonic portrait in which the artist wanted to shock with his Saturn's gaze, a purposeful frown, and rolled back eyes. For others, it was a portrait of a man who was suffering, was mentally broken, but also experiencing physical pain. The response as to what was the reason for this breakdown is once again provided by Baglione. He writes of the disappointment that the painter was experiencing after he was told that he would be awarded a noble title and a medal for his achievements in the field of art from the prestigious Portuguese Order of the Knights of Our Lord Jesus Christ (the successors to the Knights Templar) but at the last moment he was betrayed by his friend and student (Gaspar Celio), who took the title for himself. The title was probably important for the ambitions of Borgianni but was it that important? The self-portrait is also reminiscent of another painting completed by the artist entitled Democritus, showing the erudite and scholar ridiculing the human pursuit of sensual pleasures. In it Borgianni portrayed himself.

In another self-portrait (from 1615) we can see a calm visage but the same, full of melancholy eyes. Borgianni is already aware of his incurable disease (tuberculosis) and impending death, which will come several months later.

The artist’s paintings in Rome:

- Holy Family with St. Elizabeth, the Young St. John the Baptist, and an Angel, 1606? – Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

- Charles Borromeo Adoring the Trinity – sacristy of the Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

- The Martyrdom of St. Stephen, The Messengers of Constantine Call on St. Sylvester, 1610 – Church of San Silvestro in Capite

- Charles Borromeo Visting the Plague-Stricken – Curia Generalizia dell’Ordine della Mercedario

- Christ on the Cross – Church of Sacro Cuore di Gesù al Castro Pretorio

- Portrait of Carlo Saraceni – Accademia Nazionale di San Luca

- Portrait of Tomasso Laurenti – Accademia Nazionale di San Luca

- Self-portrait, 1614-1615 – Academia Nazionale di San Luca

- Self-portrait, 1615 – Galleria Nazional d’Arce Antica, Palazzo Barberini

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !